Learn Unix Online with Jupyter lab¶

You can use the Unix command line to interact with your mac, with any supercomputer or any linux system. Learn three important commands and build on those.

Bash (born again shell) is a very common shell (command line interface). You can even download Bash for Windows! Here I will walk you through some basic commands using an openly available online resource called Jupyterlab. JupyterLab is evolving quickly, so they periodically change the icons and move stuff around. I’ll try to keep up with these interface changes (You can check the Date Updated above to see how stale the information is). If the interface has changed while I wasn’t paying attention, forge ahead…everything should be the same once you figure out how to open a terminal window.

Go to Jupyter.org/try, which includes a free online unix terminal.

Click Try JupyterLab.

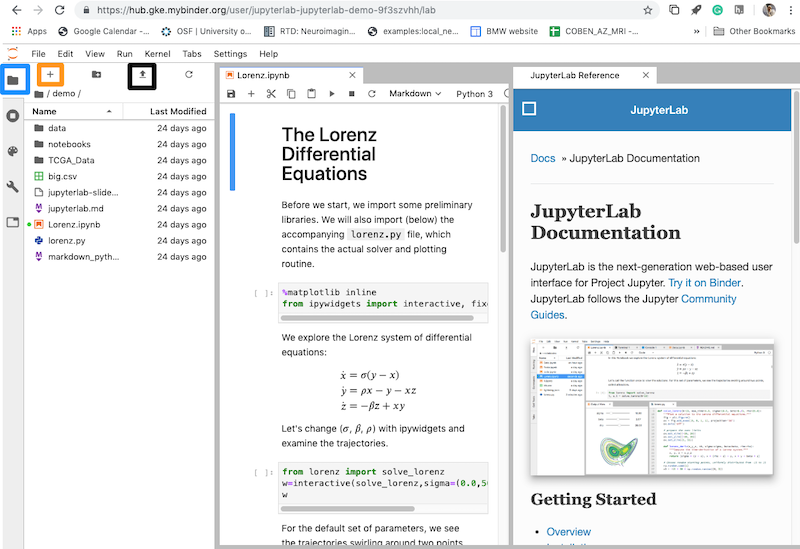

You will see an interface like this:

Note the icons on the upper left. Blue Box: This is the Files icon. Click it to see what happens: You should see it toggle the lefthand pane that lists the available files on the site. You will need it later. Orange Box: This is how you add a new launcher. You will need this in just a moment. Black Box: This is how you upload files. Keep it in mind for later. Add a new Launcher by clicking the + sign in the orange box.

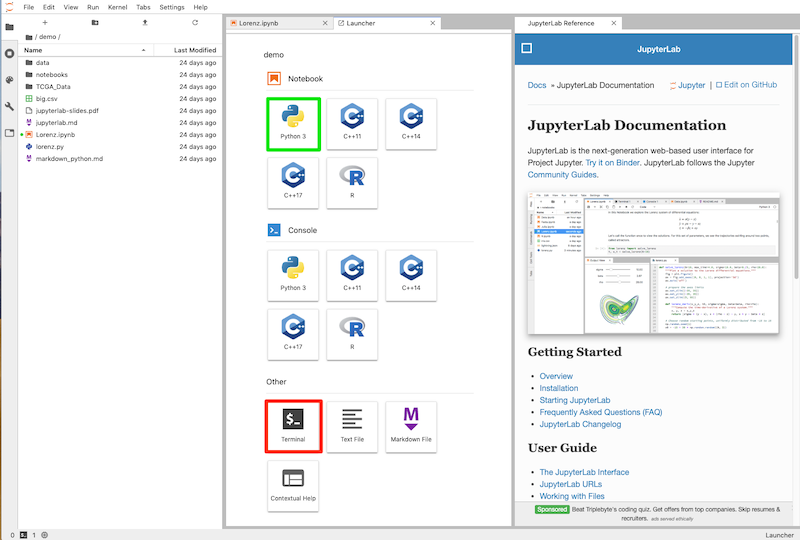

On the Launcher tab, click Terminal (red box) from the Other category.

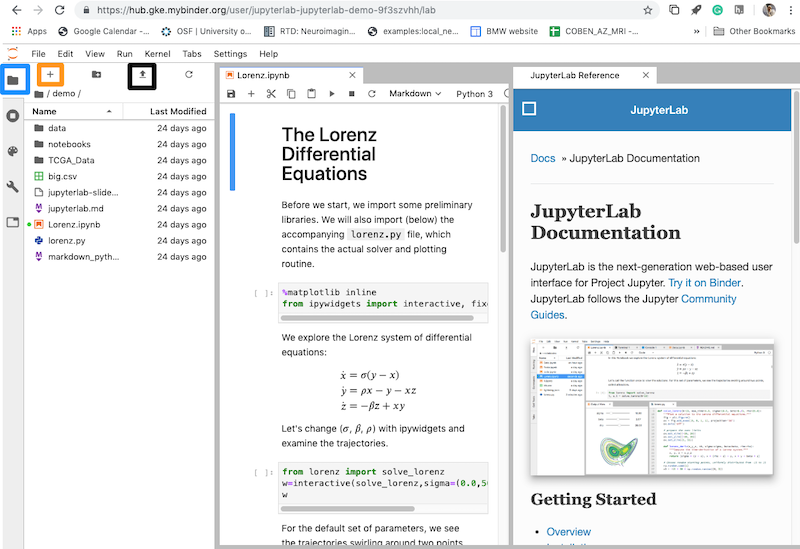

Your jupyterlab terminal displays a Bash command prompt where you can type commands. Your command line will probably look a lot like mine: jovyan@jupyter-jupyterlab-2djupyterlab-2ddemo-2d9fn107tw:~$

In the rest of this tutorial, commands that you should type are set off like this:

ls

Throughout the tutorial, you will also see questions in bold. You should try to answer these questions. You are now ready to try the basic commands explored below.

Three Commands to Rule them All¶

| Command | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| pwd | Print Working Directory | pwd |

| ls | List | ls |

| cd | Change Directory | cd / |

Find out what directory you are working in:

pwd

List the contents of this directory:

ls

Go to the root directory (there is a space between the command cd and the destination / ):

cd /

List what is in the root directory:

ls

Flags and Arguments: Examples with ls¶

Goal: You have just used three different commands. Learn to use command flags and arguments to expand your options.

At the prompt, one types commands, optionally followed by flags and arguments. Always start a command line with a command. A flag is a dash (-) followed by one or more letters that add options to that command.

list all: list all files and directories, including the hidden ones that start with a dot:

ls –a

list long: distinguishes directories, files, and links; and provides ownership and permission information:

ls –l

list all, long:

ls –al

An argument is what the command operates on, usually a file or directory.

Give ls the argument /etc to see a list the files and subdirectories in that directory:

ls /etc

Get Help¶

Goal: Learn how to find help for any command.

Unfortunately, the Jupyterlab terminal does not offer man (man=manual) pages, but you can google man and any command to find help on that command (on most real systems, you can type man ls, for example, to learn about the ls command).

Google man ls to see all the flags for ls.

Directories, Links and Files¶

Goals: Learn to distinguish different types of items listed by ls

From the root directory, type:

ls –l /etc

To distinguish directories from links (aliases) and files, look at the 10 characters at the start of each row, e.g., drwxr-xr-x. The first character d in this example tells us the item on this row is a directory. Next, the character string tells us the user, group and other permissions (as in the table below). For right now, we care about the first character, the d, that indicates this is a directory. You will also see - to indicate that an item is the default, a file; and l to indicate that an item is a link.

| File Type | User permissions | Group permissions | Other permissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| read write execute | read write execute | read write execute | |

| d | r w x | r - x | r - x |

Type cd with no arguments, and bash takes you home:

cd

Another useful command is file, type the file command followed by the argument * which means everything/anything:

file *

Unix tells you something about each file and directory in the current location.

Directories¶

Goal: Find out where you are and move around in the directory structure.

Use pwd to determine your current location. The location is displayed as a path.:

pwd

Return to your home directory using this trick (cd with no argument):

cd

Make a new directory named test:

mkdir test

How would you change directory to go into the test directory? Do so.

To find out if anything is in the test directory, type:

ls –la

. and ... means here.. means one level up.Use cd to go up one level, like this:

cd ..

What directory are you in now?

Does the following command do anything? Why?

cd .

These commands you’ve been typing are all files on computer. Where are these command files? To find a command on your system, use which:

which pwd

pwd is in /bin with many of the other commands on the system.

/bin/binWhat kind of file is pwd?

file pwd

You can use a command called history to list the commands you have run! Usually, history is set to remember between 100 and 1000 of your most recent commands:

history

Pick one of the commands and run it again from your history using the exclamation point (a.k.a. bang) and the number of the command in the history, e.g.,:

!4

Summary of Main Points¶

- You learned some commands:

- pwd (print working directory);

- ls (list)

- cd (change directory)

- file (display more information about the type of file)

- mkdir (make a directory)

- You learned about flags and arguments.

- You learned that files and directories can be hidden by naming them with an initial

. - You learned that there is a manual page for most unix commands. Normally, you can access the manual page at the command line. Sadly, the Jupyterlab terminal does not have a man page, but you can google the man page you want. If you are in a shell that displays man pages, then you can use the down arrow to see more of the page, and you can type

qto quit the man page. - You learned that you can view the history of commands you have typed, and rerun them.

What’s in that File?¶

Goal: Learn to view and edit the contents of a file.

Go to your home directory:

cd

Use cat (cat=concatenate, but is often used to view files) to view the README.md file in your home directory. Let’s be lazy and use tab completion so we don’t have to type the whole name:

cat REA

Now hit the tab key to complete the command. If the completion looks correct (it should), then hit enter to execute the command.

Let’s create a bash script. Start a new launcher if you need to (+ in orange box, upper left).

Click the Text Editor button.

In the editor, enter these 4 lines:

#!/bin/bash

echo "what is your name?"

read answer

echo "hello $answer!!, pleased to meet you."

- Rename the file to hello.sh (you can right-click the name of the file in the tab or in the file browser on the left.

- Because you renamed the file with the

.shextension, the editor now understands that this is a bash script, and it uses syntax highlighting to help you distinguish commands, variables and strings. There are 2 ways to run your script.

Try this one:

bash ./hello.sh

Later, you will change the permissions on the file, and that will make running it even easier.

Summary of Main Points¶

- You have learned to use tab completion to reduce typing.

- You’ve used

catto view the contents of a file. - You’ve used a code editor to type in text and see highlighting appropriate for the syntax of the programming language you are working in (you were writing in bash here).

Permissions¶

Goal: Learn to read file permissions and understand how and why to change them.

Remember those permissions we saw earlier in the table? Permissions are meant to protect your files and directories from accidental or malicious changes. However, permissions are often a significant obstacle to sharing files or directories with someone else and can even affect your ability to run scripts.

Let’s see the permissions on hello.sh:

ls –l

- They look like this:

-rw-r--r--. - This says hello.sh is a file

-. - The user can read and write hello.sh, but cannot execute it

rw-. - Other people can only read hello.sh

r--, but cannot write to it or execute it. - No one has

x(execute) permissions on hello.sh.

Try to execute the script:

./hello.sh

Change permissions on hello.sh and make it executable by user, group and other:

chmod ugo+x hello.sh

This changes the mode of hello.sh by adding x (executable) for everyone (chmod a+x hello.sh will also work. a=all):

ls –l

We are going to run hello.sh again:

./hello.sh

hello.sh should ask you your name and then greet you.

Let’s use cat (concatenate) to read hello.sh:

cat hello.sh

Now use chmod to remove read permissions for user, group and other on hello.sh:

chmod ugo-r hello.sh

- Look at permissions on hello.sh now

- Use

catto read the contents of hello.sh again. You no longer have permission to read it.

How do you use chmod to make hello.sh readable again?

Summary of Main Points¶

- You have learned that permissions are important.

- You learned the command

chmodfor changing the permissions of user, group and other. - A constant annoyance on unix machines you share with other people is that files and directories get created by one person, but the permissions don’t allow someone else to work with the files. So it is really important to look at the permissions when you get a

permission deniedmessage.

Standard Unix Directory Structure¶

Goal: Learn about the important directories you can expect to find on any unix system. Learn to better understand navigating those directories by understanding the path, especially whether it is relative or absolute.

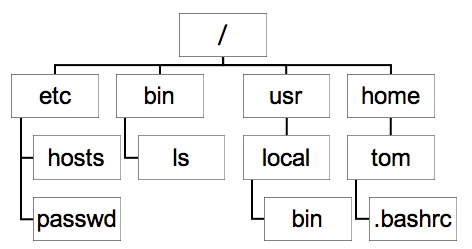

Unix directories are organized into a tree with a root (/) at the top and branches underneath containing directories and files

Important Directories¶

/binwhere many built-in unix commands are kept/etcwhere system profiles are kept; e.g., hosts, passwd, …- hosts is like a telephone book for computer IP addresses and names.

- passwd stores the encrypted passwords of all users.

- Only the root user has the ability to modify files in

/etc.

/usr/local/binwhere non-built-in programs often get added~is your home directory: where your profiles are kept and where your command line starts

How would you look at the contents of the hosts file?

The Path¶

- A path is a recipe for navigating the directory tree. You must follow the branches.

- When you use

cdyou must give it a path as an argument. - The shell has a list of paths where it looks for commands. This list is refered to by the variable name

PATH

Use echo to display the contents of the variable PATH (Variables can be identified with an initial $ sign):

echo $PATH

What is the first directory in the shell’s path? (directories in the path are separated by colons)

If commands with equivalent names (e.g., ls) exist in different places in the shell’s path, the first one will always get executed. If you install new software on your unix system, and then a command stops working as expected, you should check to see if a command of the same name has been added by the new software. That is, ensure you are running the command you think you are running, rather than a new one with the same name. For example, if a command called ls was overriding your /usr/bin/ls, you could find out by typing:

which ls

Absolute and Relative Paths¶

- An absolute path specifies the entire path starting with root. For example, the absolute path to the

.bashrcabove is/home/tom/.bashrc. If I am in the directory home already, then I may prefer to use the relative path:tom/.bashrcjust because it is less typing. - What is the absolute path to the file passwd?

- If I am in the directory /etc, what is the relative path to the file passwd?

Actions: cp, mv, rm and wildcards¶

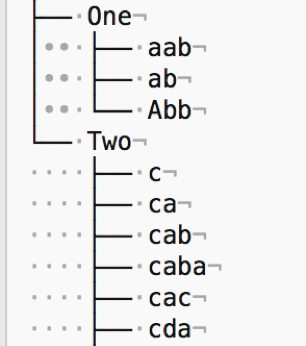

Change directory to your test directory. Under test we’ll create a structure like this:

Create the directories One and Two:

mkdir One Two

Create files in each dir using touch:

touch One/{aab,ab,Abb}

touch Two/{c,ca,cab,caba,cac,cda}

Ensure that everything has been created correctly by using ls recursively to look at subdirectories:

ls -R

Use echo and the redirect symbol > to add content to some of the files. This will help us keep track of how the files are getting moved and changed:

cd Two

echo “what is a caba?” > caba

echo “I am the cutest” > cute

You never created a file named *cute*. Do you have one now?

Copy or move a file to another file:

cp ca caba

What’s in caba now?

mv cute caba

- What is in caba now?

- Where is cute?

- How are copy: cp and move: mv different?

- Why do cp and mv require two arguments?

Move a file up one level in the directory structure:

mv caba ..

- Where is caba now?

- How would you copy caba into the directory One?

- How many caba files now exist?

- What is the absolute path to each caba file?

Copy or move a directory:

cp Two One

Did it work? (Use ls -R to see what happened). If you are inside the directory Two when you type this command, bash cannot find the directory Two. If you are above the directory Two (i.e., you are in test), it still fails. To copy a directory, you must issue the command recursively. Try this:

cp -R Two One

How is copying a directory different than copying a file?:

mv Two One

How is moving a directory different than copying it?

Rename a Directory¶

mv works differently when the target directory (i.e., the 2nd argument) does not exist:

mv Two Three

- What happened to Two?

- Move the directory Two from inside of One to test. What commands did you use?

Learn about Wildcards¶

Use wildcards: ? = one character; and * = any number of characters):

ls ca?

Which files are listed? Why?:

ls c*

Which files are listed? Why?:

ls c?

Which files are listed? Why?

Learn about remove rm¶

Remove ab from the One directory (this command assumes you are in the One directory):

rm ab

Remove a directory (How is this different than removing a file? Where do you have to be in the tree for the command to work properly?):

rm –r Three

There is NO UNDELETE on unix. Be careful with cp, mv and rm.

Permissions Again¶

Now that you have created a tree of files and directories, you may want to control who can get to it. To make sure a directory and all of its files and subdirectories are readable by everyone, do this:

chmod –R ugo+rwx One

This recursively -R changes permissions for user, group and other (ugo) to add read write and execute permissions (rwx) to the directory One and all of its contents. The recursive flag –R (and sometimes –r) occurs for many commands.

Summary of Main Points¶

- You have learned to move, copy and remove files and directories.

- Files and directories cannot be retrieved after being removed, so BE CAREFUL: Use

cpinstead ofmv, to reduce the chance of losing things. - Consider making a test directory like this one to make sure you know how the commands are going to affect your files.

Glossary of Commands¶

- bash

- cat

- cd

- chmod

- cp

- echo

- file

- history

- ls

- man

- mkdir

- mv

- pwd

- rm

- which

To learn about creating your own script directory and modifying the path, see More Unix: Install Neuroimaging Tools.

Other Unix Resources¶

- Check out excellent tutorials and videos from Andrew Jahn on unix commands for neuroimagers.

- Research Bazaar Unix Introduction

- Bookmarked Computational Resources